Special Exhibitions

-

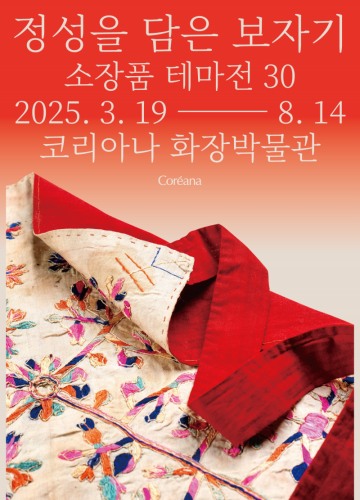

2025.3.19 - 8.14

-

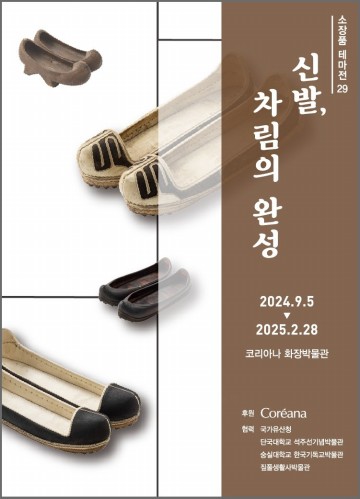

2024. 9. 5 – 2025. 2. 28

-

2023.3.2. – 6.10

This year in 2023, in celebration of its 20th anniversary, the Coreana Museum of Art is hosting an exhibition entitled TIME/MATERIAL: Performing Museology to present the works of globally renowned contemporary artist Meekyoung Shin. Since the inauguration of space*c in 2003, based on the founding mo...

-

2022. 6. 16 - 9. 30

-

2021. 11. 23 - 2022. 5. 20

-

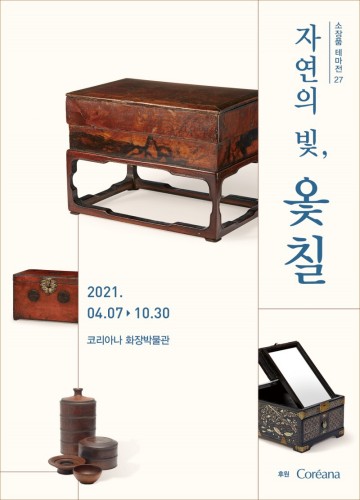

2021. 4. 7 – 10. 30

-

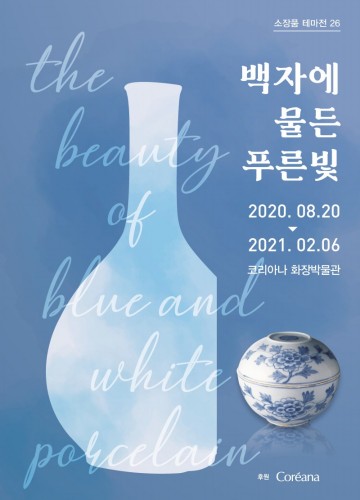

2020. 8. 20 - 2021. 3. 4

Our days are imbued in a wide variety of hues; colors accompany us on every corner of our lives. From old, white has symbolized integrity and moderation while blue has signified hope, life, and growth. Etched into the very fabrics of our diet, accommodations, and attire, these two colors were...

-

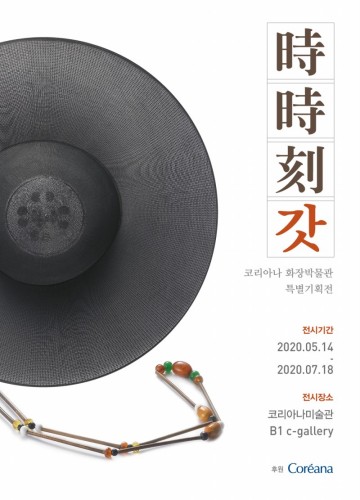

May. 14 - July. 18, 2020

Throughout our history, hats have served as a cultural marker of social status and rank in addition to satisfying practical and ornamental needs. Gat, in particular, reflects the authority and dignity of the Sadaebu(scholars who gained government posts in the Joseon Dynasty) with its wide-rangin...

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)